Over the years I have had numerous conversations with various trade workers as it relates to suitable and safe access to their work platforms when working on fabricated frame metal scaffolds. Usually these discussions are initiated after finding deficiencies and workers climbing around the scaffold like spider monkeys.

Are the end frames a safe and legal means of access? If not, when are they not? The answers to these questions depend on several factors and it has been my experience that many workers and even some safety professionals often don’t have the answers.

There are a few places where we can find those answers. The first place we can look are the Federal Safety and Health Regulations for Construction - Subpart L Scaffolds 1926.451(e). That section deals with scaffold access.

1926.451(e)(1)

When scaffold platforms are more than 2 feet (0.6 m) above or below a point of access, portable ladders, hook-on ladders, attachable ladders, stair towers (scaffold stairways/towers), stairway-type ladders (such as ladder stands), ramps, walkways, integral prefabricated scaffold access, or direct access from another scaffold, structure, personnel hoist, or similar surface shall be used. Crossbraces shall not be used as a means of access.

As we can see “integral prefabricated scaffold access” is listed as an acceptable and safe means, which means the built-in metal scaffold end frame ladders. If we look at the specific requirements for integral prefabricated scaffold access frames 1926.451(e)(6) we find that there are some additional requirements for safe access. These include:

Be specifically designed and constructed for use as ladder rungs;

Have a rung length of at least 8 inches;

Be uniformly spaced within each frame section;

Be provided with rest platforms at 35-foot maximum vertical intervals on all supported scaffolds more than 35 feet high;

Have a maximum spacing between rungs of 16 3/4 inches; and

Non-uniform rung spacing caused by joining end frames together is allowed, provided the resulting spacing does not exceed 16 3/4 inches.

The first item requires that these end frames be “specifically designed and constructed for use as ladder rungs”. Do you know if your scaffold frame was designed specifically for use as a ladder or not? What if the manufacturer calls your scaffold end frame a mason frame? Does it need to be called a ladder frame? Does it even matter what the manufacturer calls it? These are some tricky questions which might be answered by reaching out to the manufacturer and their engineering department. In lieu of getting some sort of letter or response from the manufacturer which is often difficult we can examine the history of these scaffolds. The original design for most end frames in common use today was done well before OSHA even existed, in the 1940’s, and those designs largely have not changed. There are now basically 3 different frame design standards in the United States that dominate the market. These include Safway Scaffolding type frames (Blue), Waco (Red), and BilJax (Yellow).

These three types dominate the industry and are similar in specs but do vary and should not be interchanged. Most imitators have design specs that match one of these three. The original mason frames were not designed with the intent of being used as an access point and the spacing of the horizontal bars on the end frames was mostly for ease of masonry installation and placing scaffold planks. Blocks were generally 8” in height and stacked 2 blocks high with mortar worked out to an ideal spacing of 16 ¾ inches for the vertical bars but spacing varied generally between 16” and 20” and wasn’t always uniform. Walk through frames were designed to facilitate the use of a wheelbarrow for transporting mortar and block/brick. When OSHA revised subpart L they consulted industry experts and arrived at a spacing of 16 ¾ inches for end frame ladder sections which included most designs currently in place. As such, the majority of frames met the new standards and requirements for safe access. Provided the frames met all the other requirements for access (e.g. rung length, spacing, uniform spacing etc.) they were considered designed and constructed for use as ladder rungs. In a historical letter of interpretation related to the use of integral ladder scaffolds designed and manufactured from 1957 - 1987, Fed OSHA stated that the standard “should be liberally interpreted to permit the use of those ladder systems (both portable ladders and ladders built into the scaffold frame)”. Therein it seems that OSHA was liberally construing that end frame ladder systems are designed and constructed for use as a ladder provided they meet the standard. If it looks like a proper access system it probably is. Newer designs after the OSHA standard was established are presumed to also be designed and constructed for use as ladder rungs.

54“ Scaffold - Rungs Spanning Post to Post

Related to strength, in talking to engineers from some of the leading manufacturers, most scaffolds as typically used also meet the design standards. A one inch rung is typically designed for a 250 pound worker and easily falls within the 4:1 safety factor. 1 ¼ inch or larger rungs are obviously stronger. A worker that is 350-400 pounds will approach the 4:1 safety factor on a 1 inch rung on scaffolds with rungs that extend from pole to pole on a standard 5’ frame, which is a design that is less common. Most manufacturers that have rungs that span from pole to pole have shorter spans such as 2 or 3 feet or larger rung sizes. If the rung span is only half the span of the entire end frame (e.g. a ladder section with a walk through portion) those 1 inch rungs are more than adequate in strength.

Obviously, we need to ensure the scaffold is designed for the intended use and an end frame scaffold with 1 inch bars that extend from pole to pole may not be suitably designed and constructed for the routine use of a worker who is 350-400 pounds. In that same scenario we would of course also need to look at the scaffold in its entirety including platforms and their similar 4:1 strength requirements but that is a different conversation. This all said, it is generally presumed that for typical use and set-up, that a standard scaffold end frame in use today meets the requirement to be specifically designed and constructed for use as a ladder rung.

Rungs less than 8” in length

The second threshold to pass for safe access is that the rung length needs to be at least 8 inches in length. This would exclude many types of walk-through end frames with rung lengths less than 8 inches as a safe means of access.

Another requirement relates to uniform spacing within each frame section but allows there to be non-uniform spacing when joining end frames together. Provided that spacing does not exceed 16 ¾ inches, those frames are also considered a safe means of access. The big three scaffold types are designed so that when properly stacked their spacing is uniform when joining end frames together. One potential cause of non-uniform spacing for end frame ladders is mixing and matching end frames with different ladder spacings.

Some manufacturers provide “ladder frames” with spacing that exceeds 16 ¾ inches. This, to me, is misleading because even though those frames are called “ladder frames” those frames cannot and should not be used as a safe means of access.

A Standard 5’ x 5’ “Ladder Frame” with 20” vertical spacing of rungs

It should be noted that for erection and dismantling, erectors/dismantlers are permitted to safely climb ladder rungs spaced up to 22 inches and non-uniform in spacing. Once the scaffold is built and assuming the spacing is greater than 16 ¾ inches, those horizontal bars would not be considered a safe means of access for workers other than erectors/dismantlers engaged in erection and dismantling.

Another criterion involves ensuring that the scaffold has rest platforms at 35-foot maximum vertical intervals on all supported scaffolds more than 35 feet high. If there are no rest platforms on scaffolds greater than 35’ high, the integral ladders system is not considered a safe means of access. Workers are not required to get off every 35 feet but they should have the ability to do so if they need to. Many scaffold designers feel that it would be safer to build scaffolds in such a manner as to require that the vertical run is broken and forces workers to get off at rest platforms to transition to the next part of the ladder and those systems would require platforms on the exterior of the scaffold to most safely break up those ladder runs.

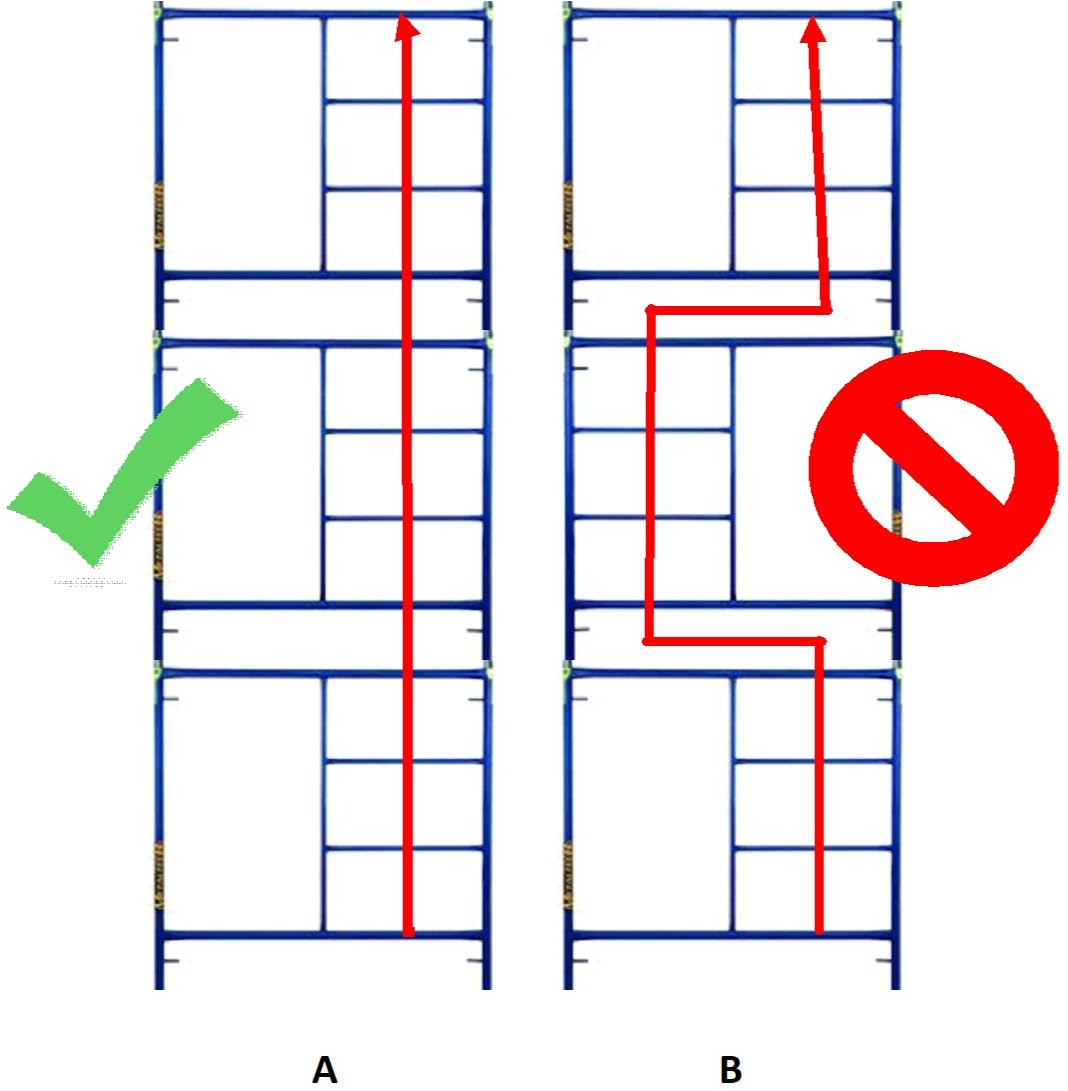

The last item in the Federal standard relative to integral ladder systems states that steps and rungs of ladder and stairway type access shall line up vertically with each other between rest platforms. What this means is that if a frame has a ladder side and a walk through side, that the ladder sides of the scaffold should all be oriented on the same side of the scaffold frame. As you can see in the diagram below, in Figure A ladder sides of the frames are all oriented on the same side and thus stacked one on top of each other. In Figure B, the ladder sides of the frame switch from right to left to right.

Obviously if ladder frames were not oriented in a line vertically, it would create a hazard from someone climbing down and if they were not paying attention and didn’t see that the rungs below were on the other side (and did not continue directly below), they could place a foot into the open space of a walkthrough section, potentially falling or worse. Similarly, the need to transition from side to side while climbing and descending introduces some further risk.

If we are to look at the ANSI standards, they essentially mirror the Federal Standard. ANSI A10.8 – 2019 Scaffold Safety Requirements states that “safe access shall be provided to work platforms of all types of scaffolds by one of the following” and then lists several types of safe access. Item #2 in that list includes “scaffold frames designed for use as access and egress methods that are secured to support the eccentric load of workers climbing these components may be used when the maximum spacing between rungs of the frame does not exceed 16 ¾ inches. The length of the rungs shall not be less than 8 inches. There shall be sufficient clearance to provide a safe handhold and foot space.”

As Fed OSHA requires, ANSI includes that the frames must be designed for use as access/egress, maximum rung spacing does not exceed 16 ¾ inches and rung length of not less than 8 inches. ANSI further specifies that the access method should be secured to support the eccentric load of workers climbing and that there be sufficient clearance to provide a safe handhold and foot space. These additional standards would forbid, for example, an access ladder on the exterior frame of a small mobile scaffold that would tip if someone climbed up on the outside. Some safety professionals and even some OSHA engineers feel that an attachable ladder on a mobile tower is not desirable for this exact reason, unless the mobile tower has outriggers or some other means to stabilize it. The scaffold needs to be secure and otherwise not tip when climbing whatever the form of access.

The second part is sufficient clearance. This basically means that the ladder rungs should have sufficient clear space behind them to allow a foot or hand to make sufficient purchase on the rung. What exactly is “sufficient clear space”? If we look at the Fed OSHA Construction Standards 1926.1053(a)(13) they provide some guidance relative to fixed ladders which is namely to maintain 7 inches clear from the centerline of the rung to the nearest obstruction in back of the ladder.

California OSHA echoes many of these same requirements and can be found in Section 1637, Article 21 of the Construction Safety Orders. Cal/OSHA requires a safe and unobstructed means of access is provided to all scaffold platforms and can be affixed or built into the scaffold by proper design and engineering. As ANSI specifies, Cal/OSHA requires the access so located that the use of the access system does not disturb the stability of the scaffold. Cal/OSHA’s rules are similar for rung spacing (max 16 ¾ inch), uniformly spaced, rest platforms at 35’ intervals etc. yet, requires rung length to be 11 ½ inches versus 8 inches. Cal/OSHA has some specific rules relative to horizontal members of scaffold end frames used for access and requires them to be reasonably parallel and level, arranged to form a continuous ladder and to provide sufficient clearance to provide a good handhold and foot space. Relative to the requirement for a continuous ladder, they reference section 1644 Metal Scaffold which states, “When only a part of the width of the metal scaffold frame conforms to ladder spacing, then these frames must be erected in a manner that makes a continuous ladder bottom to top, with ladder sides of the frames in a vertical line” which is consistent with the diagram above where ladder sides are all aligned on the same side. I have heard arguments from plaintiff’s counsel in scaffold accident cases asserting that the gap in the center vertical rail created when connecting frames does not constitute a “continuous ladder” but “continuous” per my discussions with various Cal/OSHA engineers talks about ladder rungs, not vertical bars. By this argument legal counsel is attempting to claim that basically all standard end frames in use are unsafe means of access because all have the “gap”, which is inconsistent with industry standard practice and use.

The regulation talks about ladders sides of the frames needing to be in a vertical line and forming a continuous ladder bottom to top, not sides of the ladders in the frames – an important distinction. It also ignores the first part of the sentence which states “when only a part of the width of the metal scaffold frame conforms to ladder spacing” and thus provides some context as to the meaning. Again, Cal/OSHA staff has confirmed in conversations their interpretation of this section of the regulation, namely “continuous” refers to the horizontal rungs and ladder sides of the frames, not the center post or ladder rail. The reality is workers are required to use the horizontal bars for purchase of hands and feet and unless someone had longer arms, requiring employees to use both vertical poles for their hands when climbing (versus the horizontal rungs) would require a spread of at least 2.5 feet for most standard frames and would make the scaffold awkward to climb for many people. It is far more efficient and safe to use the horizontal bars to climb versus the vertical posts. There are also no pins, crossbraces, locking devices, braces, couplers etc. that get in the way of hand placement on the horizontal rungs that would otherwise be present on the vertical posts. I am unaware of any scaffold in common use in North America that has an end frame that has a continuous center bar and thus there is always a gap present between frames. Further, no manufacturer I am aware of makes an accessory piece that fills in that gap that is commercially available, so there is no missing piece either. The “gap” is standard and safe.

Last, I need to talk about shoring end frames. These look like scaffold end frames and are often used for access but are distinctly different. Most of these shoring sections were not designed and intended to be used as an access ladder (consult the manufacturer’s instructions) and many of them exceed the 16 ¾” spacing required and thus should not be used for access.

I hope the following discussion has helped clarify when a scaffold end frame is considered a safe means of access and when it is not. Not all scaffolds are designed or built the same and it is important to ensure the scaffold in use provides all workers a safe means of access to all work levels, whatever those safe means are.